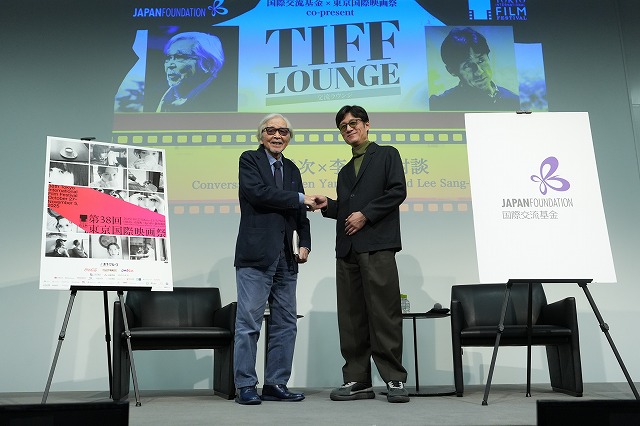

Two giants of Japanese filmmaking, Yamada Yoji and Lee Sang-il, sat down for a fast-moving, wide-ranging chat at the 38th Tokyo International Film Festival on October 30, part of the TIFF Lounge series co-presented by the festival and The Japan Foundation. While the overflow audience was predominantly Japanese, a surprising number of international attendees were present—just one more sign of the changing times for the Japanese film industry, which is no longer as “insular” as once thought.

With film critic Ishitobi Noriki as moderator, the talk unfolded between the towering creative forces, whose “connecting thread,” as Ishitobi put it, “is their direction of actors, whom they really make shine in their work.”

Yamada, newly inducted TIFF Lifetime Achievement Award honoree, is at the festival to show Tokyo Taxi, the crowd-pleasing TIFF Centerpiece film; while Lee will be receiving this year’s Kurosawa Akira Award for his body of work, especially his latest film, Kokuho. The title, which translates literally as “National Treasure,” recently became the most successful live-action film in history at the Japanese box office, having just hit 16.6 billion yen (approx. $104 million) despite being three hours long and not an animated title.

Yamada, who chairs the selection committee for the Kurosawa Award, admitted that he felt “a little embarrassed” about discussing his latest film, which has “a lighter touch” than Lee’s “marvelous film,” and repeatedly steered the conversation away from his own work to discuss Kokuho. “There are so many questions I want to ask about it,” he said.

Lee noted the sheer volume of Yamada’s filmography (91 titles and counting), and said, “I think our National Treasure is really Mr. Yamada.”

But Yamada refused the bait, plunging right in with his first question about Kokuho, which follows the friendly rivalry of two young men as they rise to the pinnacle of success in Kabuki despite one of them coming from outside that rarified world. “I’d like to ask about the structure of your film,” said the veteran director. “It’s about theater and performances, and the way you tell it is really interesting to me. Usually, if there are two male protagonists, there will also be a female and perhaps a love triangle. But not here. Instead, there’s the issue of art and hereditary lineage, and that motif is really wonderful. Did you have this structure in mind from the beginning?”

Responded Lee, “It was [author] Yoshida Shuichi’s original structure, and the contrast or conflict was what was really interesting to me. How the story would finish in the film was the question. In Amadeus, there’s this issue of jealousy –“

“That’s something you would expect,” interjected Yamada.

“– but here it’s about the artistic skill they share,” finished Lee.

“Your film is interesting because it’s not just about one man’s artistic journey,” continued Yamada. “There are ups and downs, and they occur almost in reverse — one moves up while the other moves down — with each of them facing challenges that are taking over their lives. In the end, they come to the same conclusion about [their art]. This challenge that they fight against is what makes your film so different, so profound. The two actors portray onnagata (men playing female roles), which is not something easy for an actor to do. Why did you choose that?”

Said Lee, “They worked so hard for slightly over a year in training, and even on the days we were shooting, they continued training, so altogether it was over 18 months.”

Yamada asked, “Are you saying we can play onnagata if we train only that long?”

“In the beginning,” recalled Lee, “they couldn’t do anything. It’s hard [for a novice] even to do the Kabuki foot-dragging walk. But because it was two of them, there was a healthy competition during training and it motivated them to catch up if one fell behind. We focused on rehearsing and preparing for the staged performances, and the time they spent together doing that really helped them build the necessary relationship.”

Yamada marveled, “Where did they get the energy and passion to keep working so hard for 18 months?”

“Yoshizawa (Ryo) was already becoming successful in his career, but he also wanted to notch greater achievements. I approached him 5 or 6 years ago and officially made an offer.”

Ishitobi interjected “Yoshizawa thought he’d never have a chance because he hadn’t been selected after his audition for Rage.”

“You didn’t want him for Rage?” said Yamada.

“I didn’t need a pretty actor for Rage,” Lee answered.

Ishitobi mentioned Tanaka Min’s work in the film, also portraying an onnagata, noting, “He will win all the supporting actor awards this year.”

Yamada recalled his experience casting and working with the great dancer for his first acting role, in The Twilight Samurai (2002). “I knew his physical appearance from the dancing, and then I heard his voice on a recording and felt that, with that voice and that face, as well as his incredible control of his physicality, it would work. We made the film together, and I’m so glad to see that he’s gone on to many more roles. We need [actors] for their presence, and Tanaka definitely has that.”

Concurred Lee, “He has a distinctive presence on screen. There’s something magical about the way he carries his body and his voice.”

“His physicality is wonderful,” said Yamada. “He’s quite distinctive in Kokuho, and the part matched his style quite well.”

“He was very convincing, and his gaze is very powerful,” agreed Lee. “It’s the gaze of someone who knows dance.”

Ishitobi mentioned that the story arc was very lengthy — it covers some five decades — and asked how Lee had made it compact enough to fit into a 3-hour running time.

“The initial rough cut was 4.5 hours,” admitted Lee. “We shot double that length for the Kabuki scenes. Usually I go at least one hour over the planned runtime, so I need a very skilled editor.”

Yamada recalled, “When I was working at Shochiku’s Ofuna Studio, the runtimes were already decided. So Mr. Ozu always worked toward that length. Mr. Kurosawa would continue rolling until he was satisfied, so maybe you’re the Kurosawa type.”

“Yes, maybe. Although we could have tried a series format, I wanted to see the story on the big screen. We had to jump across the years, so we didn’t see what happened to all the characters. I wanted to create that type of dynamism.”

Ishitobi sensed an opportunity, and said, “Mr. Yamada, your film Tokyo Taxi is also adapted from an original work (the French film Driving Madeleine). How did you localize it?”

Yamada responded, “It’s not Paris, it’s Tokyo. If it’s in Japan, it should be like this.”

Said Ishitobi, “There were no scenes inside the protagonist’s house in the French version, but there was in yours, making it your signature style.”

“Whatever I make, it’s always like that,” said Yamada. “I always want that breakfast scene. I always want to start from simple scenes of life in the beginning.”

Ishitobi noted, “So you have Kimura Takuya mixing his natto —”

“Yes,” laughed Yamada, “a year after he was playing a French chef [in La Grande Maison Tokyo]. When I worked with him on Love and Honor (2006), he was so diligent. Even after he finishes shooting his scenes, he’ll stay on set. He’ll come from the beginning of the day, even if his scene isn’t until later in the day. I really respect his diligence.”

Said Lee, “I’ve had the opportunity to visit you on set, and I saw you next to the camera, closely watching the actors.”

“Actors are always conscious of the director and the camera,” Yamada remarked. “I tried acting once and it left a strong impression on me of being watched. As a director, you can’t be sitting in the next room, calling ‘Action!’ But I want to go back to discussing Kokuho. We don’t have to talk about my film.”

Lauding him for “breaking the rules” about how to film actors during stage performances, finding “a novel way of making it come alive,” Yamada asked Lee how he had shot the 3-story theater.

Lee readily admitting that they used CGI in the theater scenes. “The first floor is a set, then there’s a green screen surrounding it, since we didn’t want to interfere with the actors’ performances. The audience seats, well, that’s a secret.”

Yamada probed, “How many extras did you have?”

“About 500,” said Lee, “but not for every performance scene.”

With the floor finally open to questions, one audience member wondered how Japanese traditional arts and films can work together, since Kokuho is about Kabuki and Yamada made a movie about rakugo.

“It’s Tough Being a Man is kind of based on rakugo, which I’ve been a fan of since I was a kid,” replied the veteran. “The characters are humorous and that was the element I tried to incorporate in my Tora-san series.”

For Lee, “Many people think that Kabuki is something unapproachable, but it used to be popular entertainment, so it was always a type of art that incorporates all the human emotions. But it’s unique in that it’s based on bloodline rather than just on artistic skill.”

Asked about the opportunities for Japanese live-action film, not just anime, to cross borders, Lee responded, “I think I’m very fortunate that Kokuho has been submitted as the Japanese selection for the Oscars®, which will give me a chance to see how people respond to my work in the US. We’re 100 steps behind anime. Mr. Yamada talked about structure, and I think we could explore how to deconstruct anime and incorporate certain aspects into my own work. I’m excited about how that might work out.”

Said Yamada, “Now, even the Japanese government is supporting anime. Compared to anime, live-action film sales are tiny. It’s a sad fact for Japanese filmmakers. Seventy years ago, when I entered this industry, Japanese films had really strong momentum and were very powerful. All the great directors were making enduring masterpieces.”

“Since Korea and China weren’t making films, Japan was the film pioneer in Asia. Today, Korean and Chinese movies have made great strides. In Korea, the government has been a staunch supporter of film. I think this is a problem in Japan that requires government support. The government needs to support the industry, and I think TIFF has a huge role to play in this.”

TIFF Lounge Co-presented by The Japan Foundation & Tokyo International Film Festival

Conversation between Yamada Yoji and Lee Sang-il

Guests: Yamada Yoji (Filmmaker), Lee Sang-il (Filmmaker)

Moderator: Ishitobi Noriki (Film Critic)