Acclaimed Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh spent several years filming the indigenous Bunong people of Cambodia for his new documentary We Are the Fruits of the Forest, which had its world premiere on October 30 in the Competition section of the 38th Tokyo International Film Festival. While best known for his award-winning documentaries and narrative films focusing on the aftermath of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, his concerns for the future of his homeland extend far beyond that tragic period.

The Bunong live in highland forests in the northeastern part of the country, and the director’s purpose is to compare the indigenous ethnic group’s lifestyle today with their lifestyle in the past. The Bunong have traditionally lived off the land by tapping rubber trees for sap, cultivating rice, trapping animals, and collecting honey. They exploited the forest’s riches, but always gave back to it in an organically sustainable way. However, in recent years, large corporations have exploited these same forests in a decidedly unsustainable way by clear-cutting. In the process, they have not only negatively affected the Bunong’s lives but made the land almost worthless.

The Bunong used to get all of what they needed from the forest, but they’ve been inexorably drawn into modern life to earn cash in one way or another, which keeps them dependent on outsiders. Then there’s the encroachment of climate change, which has only exacerbated their situation by killing off species that maintained the ecosystem they rely on.

In order to show the extent of the devastation to the Bunong way of life, Panh contrasts footage that he shot with archival film. The difference is startling. In the older film, the Bunong thrive, carrying out ritual ceremonies to thank the forest and its spirits for their bounty. Nowadays, this spiritual component has been diluted by outside elements who often look down on the Bunong, viewing them as backward. In Panh’s more recent footage, much of the forest is a wasteland. Compared to even the destruction caused during the Vietnam War, the industrial effects seem more severe.

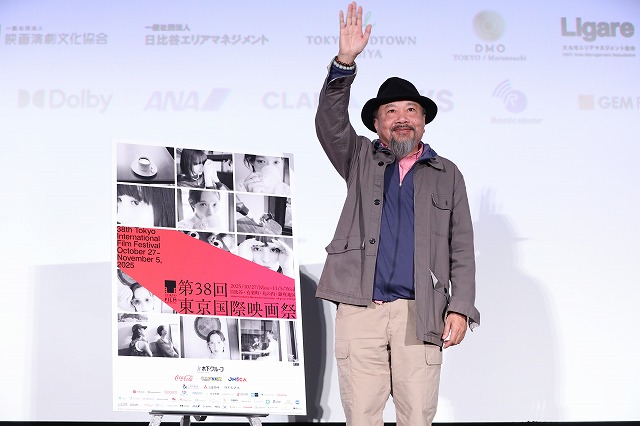

“Most of the archival material was sourced from Cinema Français,” said the director during the post-screening Q&A session. “The footage was shot in different ways depending on the time period, and there’s a lot of it. I don’t own that footage, but I found that it can be used poetically — to express ideas and make the film more engaging.”

Panh admitted that shooting the new footage took a long time. “Maybe too long,” he remarked. “It was necessary because it took time for us and the Bunong to get to know each other. There are also many ceremonies throughout a given year and we couldn’t be around all the time to shoot them. There were issues with budgeting and timing, as well. So we couldn’t be on site with the Bunong as much as we wanted to. These rituals and songs are very important to understanding their lives, and I realized that this may be the last generation who will know them and continue to carry them out. They are quickly disappearing.”

Despite the dire import of the narration, which is provided by the subjects themselves, and the destruction depicted in some of the newer images, the film is often quite beautiful, as several audience members commented. In order to make the contrasts between past and present more vivid, Panh makes extensive use of split screens.

“It’s not a style I normally employ, but I liked it here,” he said. “When I was younger and made reality films, I didn’t include narration or collage effects, but now that I’m older, I like to play with the images, and the split-screen method helped me arrange them so that I could show the past and the present at the same time. You can also choreograph the images more creatively. When you’re filming ceremonies, you can frame them by adjusting your distance or point of view. I wanted to use different techniques in order to participate in their process.”

Q&A Session: Competition

We Are the Fruits of the Forest

Guests: Rithy Panh (Director/Cinematographer/Editor)